Currently showing at the Design Museum in London is an exhibition of couturier Azzedine Alaïa’s creations. Tunisian-born Alaia tirelessly upheld the traditions of haute couture from his first show in the late 1970s until is final one just before his death in 2017. He worked in the tradition of the great couturiers he admired, Madeleine Vionnet, Cristobal Balenciaga and Charles James and his own work generated excitement and respect.

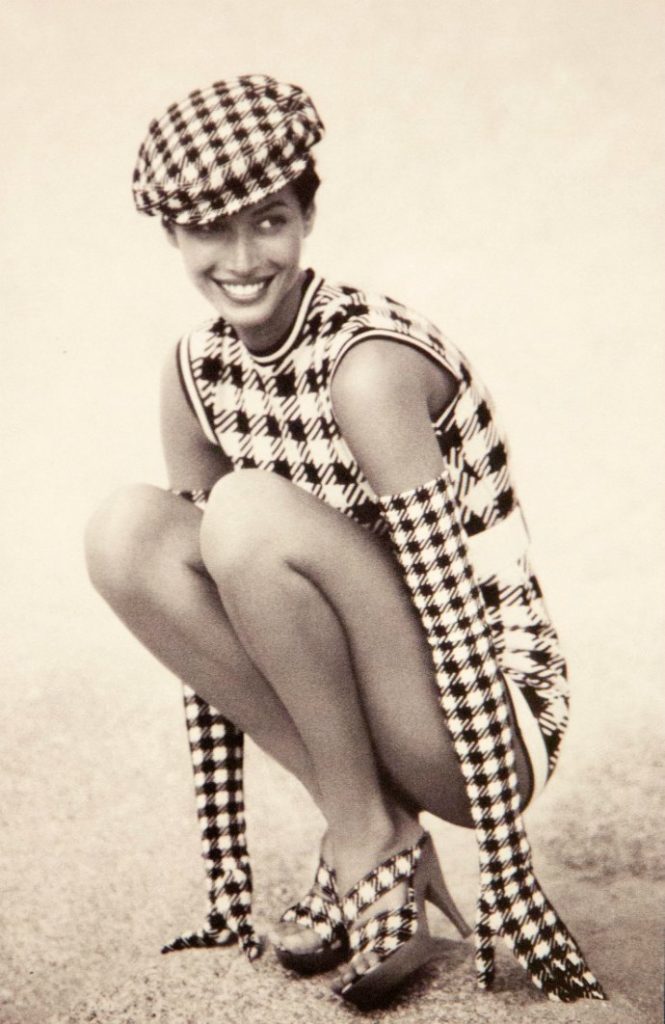

Known for his sensuous, body-hugging forms he experimented with the latest stretch materials and precisely tailored leathers. Alaïa thought with his hands and gave his ideas form by draping, cutting and pinning fabric directly onto the statuesque models with whom he loved to work.

In this exhibition, Alaïa’s most significant works are grouped to reveal ideas he perfected and remastered over many years. It’s a brilliant exhibition and I loved that the clothes were not behind glass which means you can see up close each piece from all angles and in detail.

Azzedine Alaïa began his career in haute couture – briefly at Christian Dior and then at Guy Laroche, after which he established his own fashion house creating made-to-order clothes for his clients. Today the house continues to create one-off garments for discerning customers who commit to at least three lengthy fittings to ensure their clothes are perfect. Haute couture clothes are entirely made to order, mostly by hand, and fitted individually to each client.

Sculptural Tension

“Art came first, for me” Azzedine Alaïa

Azzedine Alaïa originally trained as a sculptor at the School of Fine Arts in Tunis, and the couturier always considered his clothing in sculptural terms.

Decoration and Structure

“Material can trigger a form” Azzedine Alaïa

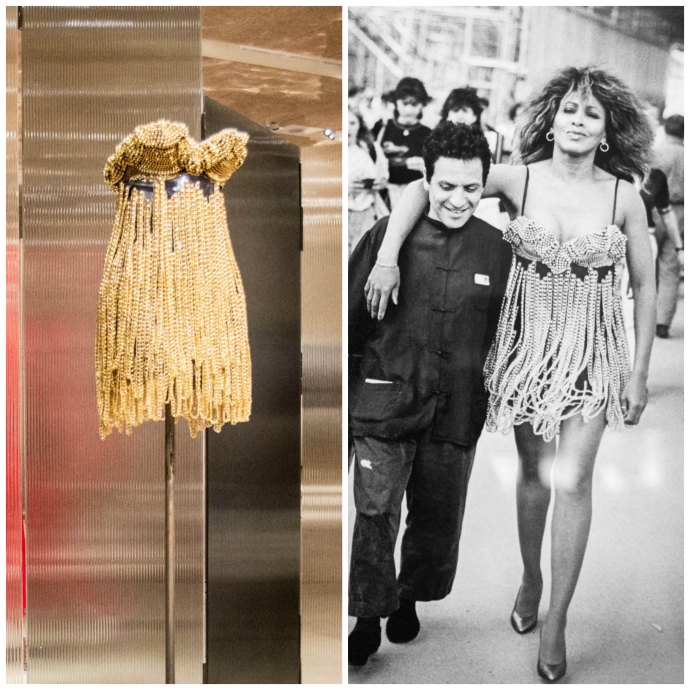

A trademark of Alaïa’s work was to avoid surface embellishments such as embroidery or applied decoration. Instead, he keyed pattern into the very fabric of his garments, making it an integral part of their structure. These decorations alter the form of a garment and change its weight. His lace garments are frequently lined in a painstakingly dyed, flesh-coloured fabric to add an illusion of idealised stage nudity.

Revolutionary Skins

“Leather is a material I sometimes wanted to make more feminine, more delicate, more fragile. I treated it in the same way as other haute couture fabrics.” Azzedine Alaïa

Alaïa translated leather from a fabric of rebellion into one of utmost elegance. The first garment that garnered Alaïa international attention was a leather coat. He returned to leather constantly throughout his career. His use of leather combined with utilitarian metal detailing as the sole means of decoration evokes industrial design, of which he was a passionate admirer.

Exploring Volume

“Making the right volume is a technique that is just as complex as any other. It demands good mathematics.” Azzedine Alaïa

These voluminous garments underline Alaïa’s life-long fascination with fashion history and his respect for the past. They re-examine the grandeur of costume in the 17th and 18th centuries, re-imagining their shapes and effects through contemporary technologies and attitudes to the body. He seldom used internal structures such as boning or petticoats, instead, exploring the qualities of the fabrics themselves to achieve deceptively complex shapes that float weightlessly around the body.

Black Silhouettes

“I like black, because, for me, it’s a very happy colour.” Azzedine Alaïa

Alaïa was admired for his highly refined Little Black Dresses and he’d use multiple fabrics with different textures in a single garment to explore their different qualities.

Black often reduced his complex, painstaking work to a graphic silhouette, disguising the extent of his labour – you had to look closer at a black dress to appreciate its intricate workmanship.

Black often reduced his complex, painstaking work to a graphic silhouette, disguising the extent of his labour – you had to look closer at a black dress to appreciate its intricate workmanship.

Alaïa said, “I prefer people to notice the woman and not her clothes”. The anonymity of black, focused attention not on the dress, but on the woman wearing his creations.

My obsession is to make women beautiful. When you create with that in mind, things can’t go out of fashion.

Timelessness

“There is an evolution, but fashion hasn’t changed so much. The body is the most important thing.” Azzedine Alaïa

Alaïa was always interested in the timeless. He constantly quoted from ancient cultures, updating these ideas with modern techniques and fabrics, re-engineering them for today’s women.

His creations were influenced by early Parisian couturiers such as Madeleine Vionnet and Alix Gres and also reference armour from ancient times.

Wrapped Forms

“I had used stretch materials for years to shape the inside of garments I made for private clients. Then I just started using them on their own.” Azzedine Alaïa

Azzedine Alaïa’s innovations in stretch fabrics were at least as important as his elevation of leather. In his hands, these transformed the silhouette of the wearer.

Rather than creating clothes anchored at strategic points – conventionally the waist and the shoulders – Alaïa’s bandage dress cling to the wearer’s form conscious of the entire body. Debuted in 1986 these variations are clearly inspired by ancient Egyptian mummification.

Rather than creating clothes anchored at strategic points – conventionally the waist and the shoulders – Alaïa’s bandage dress cling to the wearer’s form conscious of the entire body. Debuted in 1986 these variations are clearly inspired by ancient Egyptian mummification.

The dresses seem simple, but each band of fabric is precisely engineered and cut to specific dimensions, according to its place on the figure. These creations ushered in the notion of physique -delineating “bodycon” dressing, the defining aesthetic of the early 1990s.

The dresses seem simple, but each band of fabric is precisely engineered and cut to specific dimensions, according to its place on the figure. These creations ushered in the notion of physique -delineating “bodycon” dressing, the defining aesthetic of the early 1990s.

Azzedine Alaïa: The Couturier is on at the Design Museum in Kensington, London until 7 October 2018. If you can get there – I highly recommend visiting this exhibition to see Alaïa’s exquisite workmanship up close.

A wonderful review of the exhibit. I learned a lot. Thanks, Imogen

This was so inspiring and informative, thank you for sharing